In our day-to-day practice, we never know what eye disease is going to walk through the door. Whether you work in a small rural town or the hustle and bustle of the city, it is essential as an eye care practitioner to have a plan of action to be able to appropriately manage any eye emergencies that may arise. Without a triaging process in place for emergency cases, issues can arise in moments where time is of the essence.

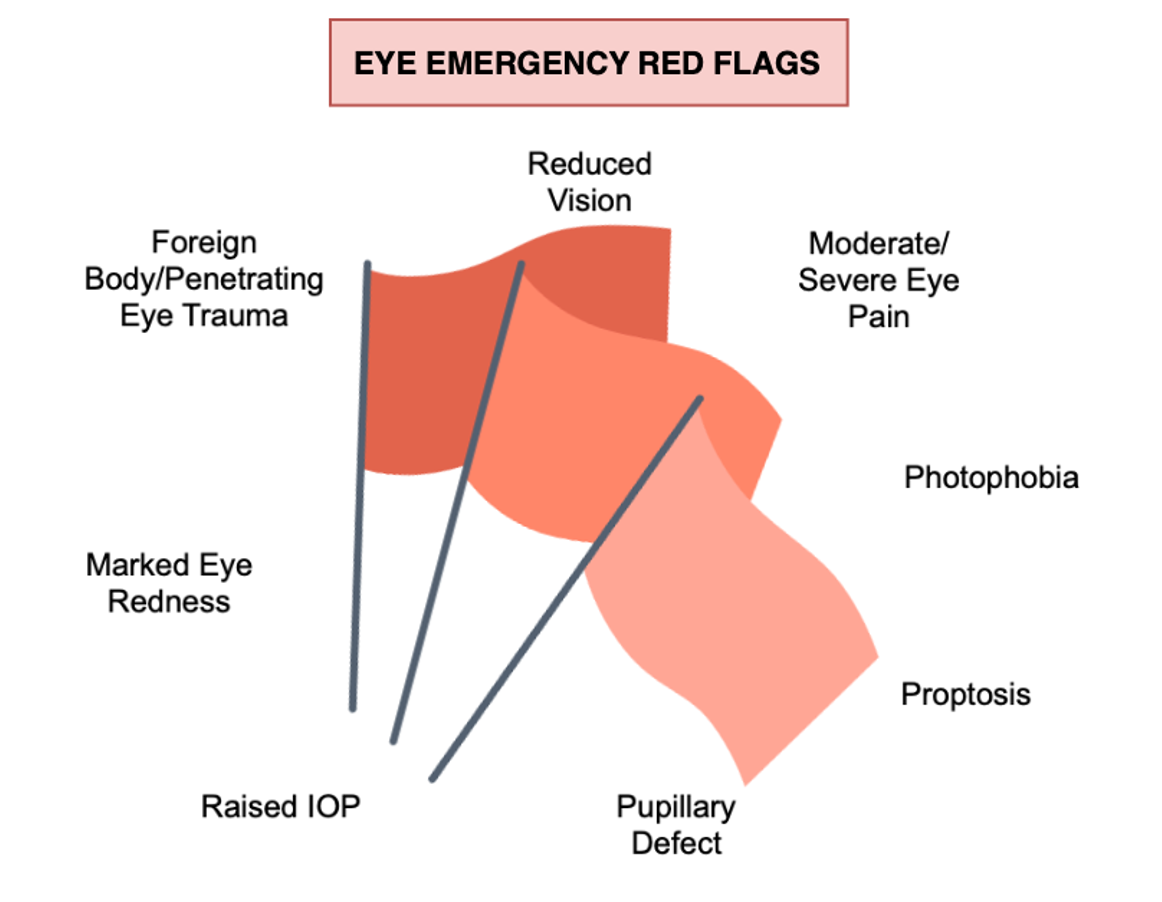

Triaging can begin at the time of appointment booking and can start from before the patient even steps foot into the practice. Training staff who book appointments to ask relevant questions and identify red flags can help determine the urgency with which the patient is to be seen. Examples of red flags include moderate/severe eye pain, photophobia, redness of the eye, reduced vision and foreign body or penetrating eye traumas as well as flashes or floaters.

Once our patient is finally in the chair, where do we start?

Case History

A thorough history and symptoms-taking can go a long way, providing us with a working diagnosis as well as guiding our clinical investigation. In many cases, the aetiology can be determined based on symptoms and presentations as well as the patients’ experience. We can uncover risk factors, if current treatments are working, relevant medical histories, medications, and pre-existing conditions, all of which can also guide possible treatments to help patients. Important questions to ask include:

Is it unilateral or bilateral?Any discomfort or pain? Is it getting better or worse? Is the pain constant, intermittent, worse with eye movements? Where is the pain located?Any photophobia?Any loss of vision? Sudden or gradual loss? Total or partial loss? What was the pre-incident vision like? E.g. strabismus or amblyopiaAny discharge? Is it clear/mucus-like/sticky/yellow?Any redness or itchiness?Any recent trauma?Any surgeries? Previous refractive surgery? Was it done overseas (missed follow-ups)?Any systemic illness? Allergies? Medications?Are they a contact lens wearer? Are they compliant or overwearing their lenses? Are they currently using eye drops? How often? When did they last use them? How old is the bottle? Are they preserved?Has this happened before?Any flashes or floaters?Any diplopia?Any headaches? Where are they located? How often? Any history of migraines/visual auras?

- Is it unilateral or bilateral?

- Any discomfort or pain? Is it getting better or worse? Is the pain constant, intermittent, worse with eye movements? Where is the pain located?

- Any photophobia?

- Any loss of vision? Sudden or gradual loss? Total or partial loss? What was the pre-incident vision like? E.g. strabismus or amblyopia

- Any discharge? Is it clear/mucus-like/sticky/yellow?

- Any redness or itchiness?

- Any recent trauma?

- Any surgeries? Previous refractive surgery? Was it done overseas (missed follow-ups)?

- Any systemic illness? Allergies? Medications?

- Are they a contact lens wearer? Are they compliant or overwearing their lenses?

- Are they currently using eye drops? How often? When did they last use them? How old is the bottle? Are they preserved?

- Has this happened before?

- Any flashes or floaters?

- Any diplopia?

- Any headaches? Where are they located? How often? Any history of migraines/visual auras?

The next step is to perform a detailed clinical examination.

Visual Acuity

It is of extreme importance to perform visual acuity testing in emergency eye cases, both as a visual measurement and for legal purposes. We must always keep in mind that a visual acuity of 6/6 does not necessarily mean nothing serious is occurring. Both eyes should be measured individually using occlusion, whilst being careful not to apply too much pressure to the covered eye. Improvement with pinhole indicates residual refractive error and a best corrected visual acuity should always be obtained in these situations.

Gross Observations

Do not forget to look at the patient as a whole! Check if there is anything immediately obvious, for example, if the eyes are at the same level or lacerations/bruises.

Cover Test and Motilities

Performing cover tests at both distance and near is important to assess for nerve palsies. Ocular motility testing is essential to ensure all extraocular muscles are working correctly. It is important to perform in cases of trauma (e.g. blow-out fractures) as well as for nerve palsies, in patients with diabetes, if any complaints of diplopia or systemic conditions such as thyroid eye disease. The Hirschberg test is simple and easy to perform and we can ask the patient to report any pain with eye movement or diplopia.

Slit Lamp Biomicroscopy

One of the most crucial parts of the red eye assessment. A systematic approach is best from anterior to posterior, looking at the:

- Eyelashes and eyelids (including lid eversion) - check for signs of blepharitis (anterior and posterior) or debris (cylindrical dandruff/crusting/scaling), papillae or follicles, concretions, pseudomembranes or true membranes and if any foreign bodies are present.

- Sclera/episclera/conjunctiva - check for redness and discharge.

- Cornea - check for endothelial oedema, epithelial cysts, negative fluorescein staining patterns, corneal staining (with or without stromal glow), ulcers, dendrites, infiltrates and keratic precipitates/pigment.

- Anterior chamber/angle - is the angle narrow? Is gonioscopy indicated? Perform Seidel test to check for any aqueous leakages.

- Iris/pupil - check for anterior or posterior synechiae, if iris atrophy is present and for any laser peripheral iridotomies. Is the pupil round or distorted (corectopia)?

- Lens - check if the patient is phakic or pseudophakic? Observe for cataracts or embryonic remnants. If pseudophakic, any posterior capsular opacification or dislocated intraocular lens?

- Anterior vitreous - observe if there is any pigment in the anterior vitreous (Schaffer’s sign - signifying a retinal tear/hole/detachment).

Pupil Testing

Pupil testing is a crucial assessment of both the afferent and efferent visual pathways. We test for direct pupil responses as well as consensual, with the swinging torch test used to determine if a Relative Afferent Pupillary Defect is present. We must also measure the difference between pupil sizes in light and dark illumination as this can be used to diagnose certain conditions such as Horner’s Syndrome.

Intraocular pressure

Intraocular pressure is necessary to measure, with a normal range of 10-21mmHg and a difference greater than 2mm serving as a prompt for further investigation. High intraocular pressures can be indicative of acute angle closure, ocular hypertension, primary and secondary glaucomas (e.g. neovascular glaucoma) as well as certain types of uveitis (e.g. Posner Schlossman). A lower eye pressure in the affected eye could also be a sign of uveitis.

Gonioscopy

Gonioscopy is important to assess the anterior chamber angle and rule out angle closure. Check out our blog on gonioscopy here for further information: https://www.yoptoms.com/Blog/10498873

Ophthalmoscopy

We must always look at the posterior eye, dilating when indicated to rule out certain sight-threatening conditions such as retinal detachment or intraocular foreign bodies. A systematic approach involves assessing the optic disc, macula, blood vessels and retina both centrally and peripherally.

Infection Control Procedures

Many ocular emergencies present as a red eye. With any red eye assessment, we must keep in mind certain procedures and precautions throughout the examination. These include washing our hands, wearing gloves if required, cleaning equipment using alcohol wipes as well as using minims or strips for assessment to avoid contamination (dilation drops and anaesthetic drops) and using separate tissues and fluorescein strips for each eye in case of viral infections.

Sight-threatening and life-threatening emergencies can manifest in many ways. Below is a summary guide of the Australasian Triaging Scale, a clinical tool used by emergency clinics such as Sydney Eye Hospital to determine the maximum waiting time for certain eye emergencies.

Triage Category 1: Immediate referral for life-threatening conditions.

Triage Category 2: Assessment and treatment required within 10 minutes, otherwise sight-threatening. Examples of conditions include chemical burns (irrigation to be initiated from the outset – no waiting!), penetrating eye traumas (place shield if possible), sudden painless vision loss (Central Retinal Arterial Occlusion) or severe ocular pain (acute glaucoma).

Triage Category 3: Assessment and treatment required within 30 minutes. Examples of conditions include painless vision loss (Central Retinal Vein Occlusion), presence of a hypopyon and an ‘8-Ball’ hyphema (total anterior chamber filled with blood). In these instances, there is a potential for adverse outcomes or relief of severe discomfort.

Triage Category 4: Assessment and Treatment start within 60 minutes, otherwise there is a potential for adverse outcomes or relief of severe discomfort. Examples include corneal foreign bodies (non-penetrating), painful red eyes, flash burns (secondary to welding), retinal detachments (with a positive history for trauma/injury) or a smaller hyphema.

Triage Category 5: Assessment and treatment within 2 hours. These conditions are less urgent and tend to be chronic or minor in nature. Examples include conjunctivitis, blepharitis, chalazion or dry eyes.

Cases of red eye are common in optometric practice and there can be a myriad of causes, some mild in nature that require chronic management and others acute that require immediate attention. If a patient presents with any of these red flags, same day referral to an ophthalmologist may be required.